June 17, 2017

It does not matter how friendly we are, how much we might individually be beloved by our family, our co-workers, or schoolchildren whose days we brighten, in any given encounter with the police, we are seen as nothing more than a dangerous Black body, engendering mortal fear by our very existence, justifying deadly force by just being. We are penalized for venturing outside of the designated, circumscribed, crumbling spaces carved out for us in undesirable corners of inner cities, until they become desirable again and we are chased out by “stop and frisk,” or priced out by “redevelopment.”

The truth is, far too many people in this country have no use for Black people now that our labor is not free. We suffer widespread employment discrimination, yet are castigated as lazy if we are unemployed. We have been redlined out of home ownership, yet the crumbling state of many of our neighborhoods is laid at our feet. We are hated because our presence is an unwelcome reminder of the price of American prosperity.

Those of us who succeed despite these formidable barriers, know the knife’s edge on which we sit. If the music is too loud at our suburban house party, we risk being hauled off to jail, rather than just receiving a summons. If our teenage girls go to a pool party, they could be pinned to the ground in their bikinis by an overzealous cop. We are terrified every time our young adult children get behind the wheel that they will end up like Jordan Davis or Sandra Bland or Philando Castile.

Before Philando Castile was murdered, with his girlfriend and her four-year-old daughter in the car, he was stopped 49 times by the police. Let that sink in for a moment. In thirteen years, he was stopped on average once every three months for low-level infractions like an unlit license plate. (Source: The New York Times). The ACLU found that, in Minnesota, Black and Native American people were eight times more likely to be charged with a minor infraction than white people (Source: The New York Times).

These disparities are nothing new, but Black people naively hoped that data and technology would force a reckoning. Instead, we are confronted with the stark truth that even when there is video showing us murdered in cold blood, white jurors will contort their thinking to justify the actions of police officers, and exonerate them, time and time again. And when we exercise our First Amendment right to protest this injustice, we are met by cops in military gear who treat Black citizens like an invading army in our own country.

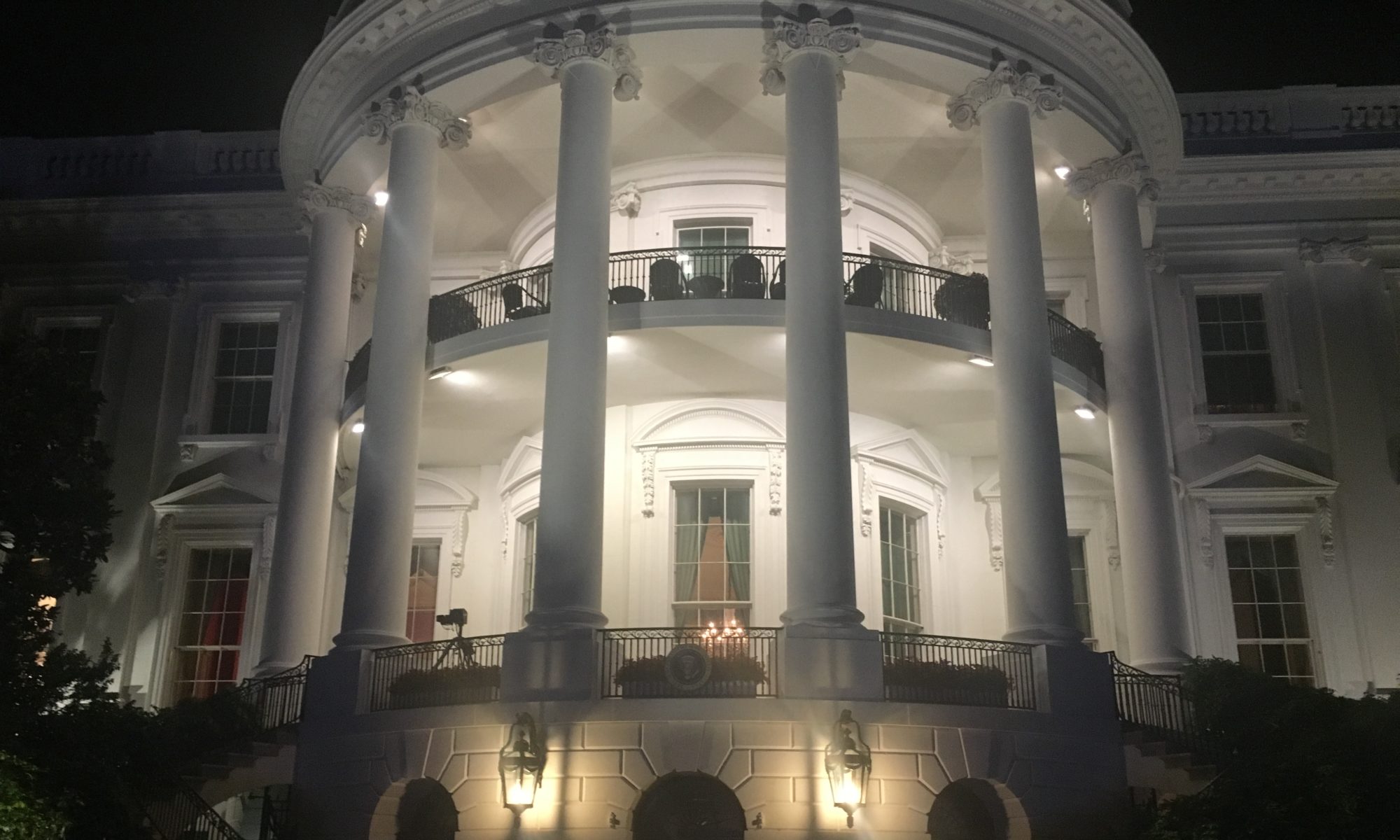

Sadly, the irrational fear and hatred of Black people is pervasive and inescapable, like weather. We seek solace in our churches. We snatch joy from our music, from Miles Davis to Beyoncé. We take pride in our accomplishments, from “hidden figures” Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan and Mary Jackson to President Barack Obama. But on a day like yesterday, when we are brutally reminded of how little our lives matter, it is enraging and exhausting. Although we will resume the fight, our white brothers and sisters must join us. Because the truth is, as Valerie Castile said, “When they get done with us, they’re coming for you.”